Why do we even use it?

|

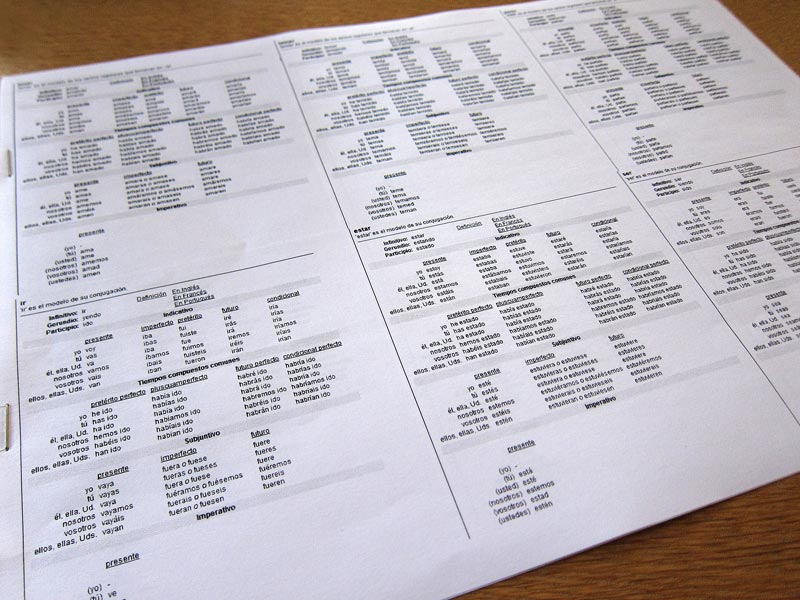

| English can do without the subjunctive, Spanish can’t! Photo credit: Mace Ojala licensed CC BY-SA 2.0 |

I wish you were here

If I were an astronaut, I’d fly to Mars.

They have asked that she remain silent.

The were in the first two examples and the remain in the last are nothing but subjunctive. See? Told you they’re not entirely alien after all! The only difference is that in English, they’re not as commonly used as in Spanish. In fact, there are quite a few situations where the subjunctive form can be used in English but isn’t unless the intent is to sound super-prudish. Look at this:

I want that your mother take her medicines on time.

This sentence reeks of linguistic snobbery, doesn’t it? No wonder why most people would prefer to go with the following variant instead:

I want your mother to take her medicines on time.

This was the non-subjunctive way to convey the same message. So you see, most cases of subjunctive in English have fallen out of favor with time but the same hasn’t happened in Spanish. In Spanish, subjunctive isn’t a sign of old-school literary pedantry but a day-to-day necessity. The above example where you had a non-subjunctive alternative to the subjunctive construct would necessitate a subjunctive when translated to Spanish. For a more dummy-friendly and tricks-loaded discussion on this mood, read up this article on the Spanish subjunctive and ojalá

Imperfect subjunctive is when you use subjunctive in the past tense. Instead of trying to explain it in a thousand words, I’ll give you a few examples:

If I were a teacher, I would teach you.

I hope she took her pills on time.

They ensured that I didn’t die.

All three of the above scenarios are in the past tense and hence the mood is imperfect subjunctive. So, without any definition or grammatical description, you should now be able to tell this creature from the others.

The imperfect subjunctive conjugation

I know you’re impatient for the memory trick already but bear with me. In order to understand and appreciate the sorcery we’re about to see, it’s imperative that we first understand what it is that we’re trying to nail with the trick, i.e. the conjugation itself. So, in order to quickly get that out of the way, here’s what the endings for the Spanish imperfect subjunctive look like:

-ra (yo hablara)

-ras (tú hablaras)

-ra (usted/él/ella hablara)

-ramos (nosotros habláramos)

-ran (ustedes/ellos/ellas hablaran)

Good news is, these endings work just fine for all 3 classes of verbs (-ar, -er, and -ir).

Plot twist: There also exists a second set of endings for this conjugation! This one goes:

-se (yo hablase)

-ses (tú hablases)

-se (usted/él/ella hablase)

-semos (nosotros hablásemos)

-sen (ustedes/ellos/ellas hablasen)

What’s going on, you ask? We’ll get there in a bit, but first let’s make sure you understand that there are two different sets involved here and that memorizing them is a cinch.

The Trick

|

| Memorizing conjugation tables is no good without a lot of practice Photo credit: Keith Williamson licensed CC BY 2.0 |

So I presume you’ve familiarized yourself with the present indicative endings by now in which case, I would like to point out that save the first ending, the one for yo, all others closely follow the same pattern. Except that in this case, the yo form and the él form are identical which makes our job even easier. The tú form just takes the ending for the yo form and slaps an -s to it. The nosotros form slaps an -amos to it just as you’d expect. Everything is predictable, see?

The only bit you need to remember is the starting point. If you remember to conjugate the verb in the yo form, everything else will fall in place. So, your job is simple: Remember -ra and -se. Remembering -ra is easy; just keep the following in mind:

If I were a doctor, I’d cure cancer.

The were in the above sentence will remind you of its past subjunctive nature and the combination of were and a will cue you to -ra. Try it. The same sentence also covers -se; just focus on the last syllable of cancer. Wasn’t it easy? I am sure you can come up with less ridiculous ways to memorize this. Get creative. All that matters is that you remember them. Yeah, that last line was subjunctive too.

But the starting point is still not clear. By that, I mean the root. It’s not as simple as it looks in the case of hablar. For instance, tener becomes tuviera and not tenra. So how do we determine the root to start with? It’s simple: Just take the third person plural conjugation in the preterit tense and cut out the -ron ending. Whatever remains is your root. In simpler terms, conjugate the verb in the preterit tense, take the -ron form, and remove -ron from it. And if, by any chance, the preterit tense spooks you out, check out this post on the Spanish preterit tense tricks. It’s ridiculously easy to memorize the preterit conjugation in Spanish!

Oh, and do remember that the endings in these sets never get the stress which is why you’ll notice an accent mark in the nosotros form (habláramos and hablásemos). The accent mark is just to ensure the stress stays in the right place and doesn’t move after the conjugation.

What’s with the two endings?

This is the interesting bit about Spanish imperfect subjunctive. Pressed for time? Here’s a TL;DR answer for you: They’re both identical but -ra is what you should go with. Forget about -se; it’s rarely used, if at all.

Now the details, if you’re still here. You see, language evolves and things change with time. Once upon a time, we used thou for the second person singular pronoun in English. Today, we do just fine with you. In the case of Spanish imperfect subjunctive, -ra is the more modern cousin of -se. Don’t get me wrong, you’re free to say hablase instead of hablara and you’ll still be understood. It’s just that you’ll sound like someone from the Middle Ages. So for all practical purposes, you’d do well to just discard the -se set off your to-do list.

Other vernacular uses of the -ra form

Look at the following sentence:

I had written to her.

This is an example of the past perfect tense or, in more complicated terms, the pluperfect tense. Translating this kind of sentences into Spanish is pretty straightforward. You just use the imperfect form of haber (Spanish for have) and attach it to the past participle of the verb in question. This is exactly what you do in English, right?

Le había escrito.

But why am I telling you about past perfect when we’re discussing imperfect subjunctive? Because in parts of Latin America and in regions of Spain close to the Portuguese border, folks often use the -ra conjugation for past perfect expressions! Of course that’s a non-standard dialectical construct but if you’re planning to visit those areas, you should know. So the above example would be rendered as:

Le escribiera.

There are also some places where people use the -ra form for the conditional when haber is involved. Now what’s conditional? Conditional is when you would use would in English. And the situation we’re discussing is where you would use would have in English:

I would have done it.

She would have known.

Standard Spanish would translate the above sentences as:

Lo habría hecho.

Habría sabido.

Notice the habría in the above translations? There are people who go with hubiera (haber in the imperfect subjunctive conjugation) in those cases instead. Again, this is highly non-standard and only good to know should you ever need to visit parts of the Spanish-speaking world that practice this usage.

If you ever decide to go vernacular as in the scenarios we just discussed, do remember that it’s only the -ra form that goes and not -se.

So that’s it! Now all you need is tons and tons of practice. Memorizing conjugations is meaningless if you don’t practice enough. It’s like they say: If you don’t use’em, you lose’em. Got any more fun ideas for those pesky subjunctives (well, not quite pesky anymore I suppose)? Do share them with the rest of us in the comments below.

.png)